by Tinako, artist

[The opinions expressed in these essays do not necessarily reflect the position of ARAUNY.]

My single favorite effect of veganism is the universal compassion it has unleashed in me. I think that as long as I was using animals at all, I needed to tell myself stories about them. I feel as though I’ve now been freed from a cynicism about animals that was necessary for me to be able to eat them, a justifying or excusing for eating them that I didn’t know was there, and which was untrue and unfair. I’d like to explain how I believe this impacts my art.

We have to believe all sorts of things about animals in order to feel OK about eating them or their “products:” they’re stupid, they don’t care, they’re happy on the farm, they don’t matter. The stories I had to paste onto them got in the way of really seeing them. I saw a collage artwork once that struck me: the artist had made a large portrait of a cow out of clippings about cows. For example, one snippet read

With a…

And a…

Here a…

There a…

Everywhere a…

The last words of each line were cut off, but it was obviously “Old McDonald.” The collage was a cow made up of things we think about cows. Which is not really a cow, it’s just our thoughts. I’m not sure if the artist was aware of this wonderful ironic disconnect, this reduction to nursery songs, or if he really thought he was cleverly reinforcing the cow image with true cow information.

That was a cow so obviously made up of thoughts, but all art is interpretation. When I think about most realistic paintings that have animals in them, it seems as though the artist has brought their assumptions to the work. Perhaps cows in a field are pretty, and give one a sense of pastoral peace and comfort – cows mean plenty to eat. Chickens are so ridiculous, scratching around. Usually these animals are painted with warm, homey tones (golds and reds), and I think their purpose is to make us feel comfortable.

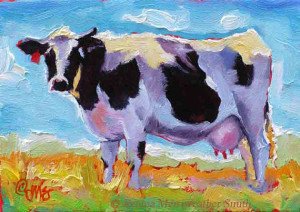

This is a typical example of farm animal art. The artist probably believes she loves cows, just as the hunter artist believes he/she respects ducks, but they are bringing their own needs to the art: this cow is tagged, full-uddered, and rather stupid-looking, its body shown but no eyes. Maybe a cow’s body is more convenient than its thoughts or feelings. Or maybe this artist is deliberately showing exactly what I’m saying: we reduce these animals to objects because we have to in order to use them. Personally, the juxtaposition of the tag with the artist’s emphasis of the beautiful, sunny field make this painting unbearably dishonest for me.

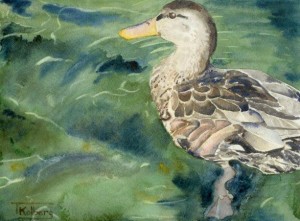

Wildlife is usually painted in cooler tones (blues) – think of hunter’s art, with the cold blues and browns of ducks in a pond. What is the artist telling us with this choice? Maybe he’s saying, “enjoy the plumage but don’t get attached – it’s a cold world and we need to kill or die.”

Compare the paintings you see in the link above to mine here. Admittedly, I painted mine in coolish colors, too, but do you think someone who kills ducks might prefer one painting over the other?

Perhaps I’m too harsh, reading too much into it, projecting my views and values onto others’ artwork without justification – could very well be, and certainly there are exceptions.

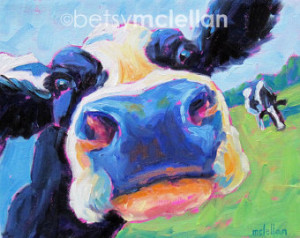

Also, things are changing – when I first started looking into this difference in 2013, the majority of cow art was as you see above – cow as landscape object; now I see many more face portraits, with character and life. I see a playfulness which I hope is not trivializing, the art version of “happy meat.” What do you think? Take a look at the different types in the link above and decide for yourself whether you can glean how the artists feel about these animals, what has been brought to the picture. Is there a difference between many of these and my art? How does this compare with art about humans, portraits vs. nudes?

I think an exception to all this is wild bird art (e.g. songbirds), which seem to usually be painted with dignity and affection – any coincidence that we do not use wild birds? You compare the songbird art to the duck hunting art and decide for yourself. Not everything follows this pattern (keep in mind that Audubon art, of any animal, is about science), but is there a trend? Why?

I’m not claiming any of these paintings are “bad art,” because I think the purpose of art is to show a particular viewpoint. I think it’s excellent that assumptions are revealed, and I’m sure my art is no exception.

How much do we really see of a cow, as she actually is? How much of it is stories and songs, ideas about cows? Do cows need to give milk? Do cows feel useful when they see happy children eating ice cream? Do cows not really care about their babies? Do we need to eat ducks? Are we really doing wildlife a favor when we hunt? We usually answer these questions in ways that meet our own needs instead of looking clearly and determining reality as best we can. Once I said no to eating animal products, I answered these questions differently.

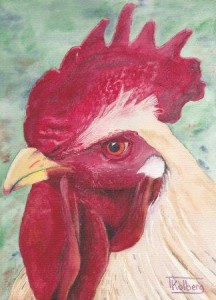

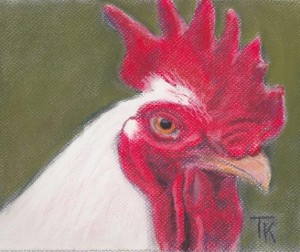

When I paint an animal, I try to really look. I don’t assume I know what it’s like to be this animal, I don’t assume he thinks like me, and I don’t assume our interests align. This isn’t a coldness, to distance myself; it’s curiosity, respect, and just knowing how little I know. When McLovin’ came running over and was checking me out, I didn’t assume he really liked me, though that would have gratified my desire to connect with him – it’s just as possible he was annoyed I was there.

I spent some time with a turkey named Whisper and took some video of her seemingly cooing to me. So sweet! When I showed the Farm Sanctuary staff, they said she was aggressive and that was her warning, like a growl. I think that is very funny, how mistaken I was! I accept them for who they are, and I accept that I don’t understand. I barely understand my dog, and I definitely don’t get my cat.

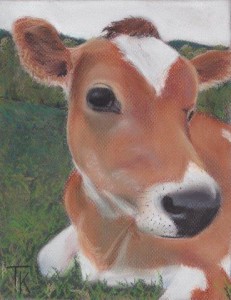

So what’s left to paint, if I don’t project my own beliefs onto them and can’t really know what these animals are thinking and feeling? What’s left is what I see; and what I see is inherent dignity, the kind of dignity that doesn’t depend on circumstances. Whether the animal is curious, annoyed, happy I’m offering back scratches, or oblivious, they have the dignity of their own thoughts, their own body. McLovin’ doesn’t have to look like he loves us (he is rather fierce-looking!); he just is who he is.

My art usually zeroes in on the face, the eyes, because I’m more interested in what the animal is thinking than what it looks like. There’s someone in there, someone worth painting, someone with his or her own thoughts, valid even though I can’t understand them. I could not have this insight if I were not vegan, if I needed these animals to be a certain way in order to feel better about my own choices.